A Return to Ireland

In 1910, Jack B. Yeats and his wife Mary Cottenham Yeats left their home Cashlauna Shelmiddy (Snail's Castle) in Devon and moved to Greystones, county Wicklow. Upon his return to Ireland, Yeats became increasingly interested in Irish political affairs. His pocket-sized sketchbooks capture the major events and protagonists of the Irish revolutionary era, including James Larkin and Patrick Pearse; the 1915 funeral of Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa; and the site of the Bachelor’s Walk Massacre in July 1914. However, he also documented the everyday reactions of ordinary citizens living in extraordinary times, such as the 1913 strikers during the Dublin Lockout; children looking at tricolour flags displayed at a tobacconist; and a conversation with a man in Greystones in the days after the Easter Rising.

That'll be a warm place to be so they say. But they say it’s settled now – though I didn’t hear what terms they came to. I don’t think [Dublin would] be a safe place yet. Indeed you might be in danger of getting a crack on the head from a bullet in there.

Jack B. Yeats’s conversation with a man in Greystones in the aftermath of the Easter Rising, 2 May 1916

Greystones, 1916

The Easter Rising lasted for six days, from 24 to 29 April 1916. Three days later, Yeats recorded a remarkable conversation with a man in Greystones, whom he met on his way into the capital. At the time, Greystones would have been relatively isolated from Dublin city centre, and although he was a regular visitor to the city, Yeats also welcomed any news he could get from those passing through the village. He was fascinated by the peripatetic outsiders that traversed the country: travellers, circus performers, and other wanderers and wayfarers. Leaning on a walking stick, with a bundle under his arm, the man in Greystones evokes the romantic ‘wanderer’ – a familiar archetype in Yeats's paintings. His idyllic portrayals of these archetypal characters were often far removed from the precarity and social exclusion experienced by many on the fringes of Irish society. The sketch also highlights the artist’s interest in capturing the words and expressions of those he met, as much as their physical appearance. The warning delivered by this anonymous stranger is a stark reminder that many civilians were killed in the crossfire during the 1916 Rising, and it is possible that Yeats postponed his trip into Dublin following this conversation.

Greystones was neither town nor country nor suburb. Our only link with the spacey world was from the tinkers [members of the Mincéirí/Irish Traveller Community] that passed along the road.

Jack B. Yeats in a letter to Padraic Colum, 26 June 1918. New York Library Berg Collection

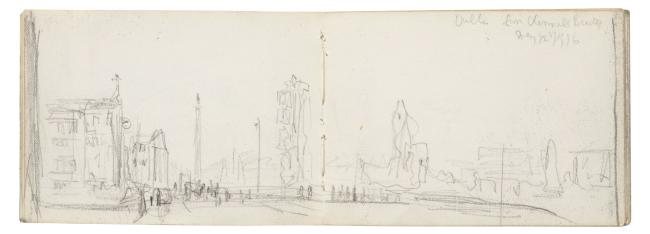

Dublin in Ruins

Ten days later, on the 12 May, Yeats observed and recorded the ruined buildings of O’Connell Street. His rapid sketch captures the bleak aftermath of the Rising; crowds gather to survey the destruction wrought by British shelling, while Nelson’s Pillar rises unscathed from the ruins. During the insurrection, key locations held by the rebels had been bombarded by the British army, to the surprise of rebel leaders who did not believe that the British would shell the 'second city' of the empire. The intended targets were Liberty Hall, the GPO and Boland’s Mill, but many shells missed the mark, destroying other buildings in the vicinity. The neo-classical headquarters of the Royal Hibernian Academy on Abbey Street was one such unintended casualty, destroyed by the British gunboat Helga on the Liffey. All artworks submitted to the 1916 RHA Annual Exhibition were lost, including three of Yeats’s own paintings: The Donkey Show, The Turning Post in the Tide, and The Runaway. An inscription on the cover of his copy of the exhibition catalogue reveals his efforts to gain compensation for this loss.

Pictures burnt. I claimed £47 5s; I received only £26 7s. Balance £20 18s.

A note inscribed by Jack B. Yeats on his copy of the 1916 RHA Annual Exhibition Catalogue

The Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund

Almost exactly a year after the Easter Rising, an auction was held at the Mansion House in aid of the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents' Fund. Following her husband’s execution for his part in the Rising, Kathleen Clarke established the Irish Volunteer Dependents’ Fund, with the goal of supporting the families of those killed or imprisoned. The Irish National Aid Association represented supporters who sympathised with nationalists but hadn’t taken part in the Rising. The two groups amalgamated into the Irish National Aid and Volunteer Dependents’ Fund, eventually administered by Michael Collins. Their activities included the distribution of food and clothes from America; delivering parcels to camps and prisons; first aid training; and fundraising through fairs, céilís, concerts and auctions.

Donations to the Gift Sale

Yeats kept his copy of the auction catalogue and even signed the cover, underlining his support for this nationalist organisation. The catalogue reveals that many Irish artists and collectors donated artworks to the gift sale – including the Yeats sisters, who presented a portrait of Padraic Colum by their father John Butler Yeats; Margaret Clarke, who donated two of her paintings; and Seán Keating, who presented his vision of heroic nationalism, Men of the West (1915). Yeats himself donated two original drawings, one of which is entitled Starting on a Long Stage in the catalogue. Interestingly, the fashionable society painter William Orpen donated a ‘Blank Canvas’, or portrait of the highest bidder. In the preceding weeks, Orpen had joined the war effort in France as an official war artist and a major in the British army; his donation to the Gift Sale at this time underscores his dual sympathies with conflicting British and Irish interests.

Further Reading

Yvonne Scott (ed.), Jack B. Yeats: Old and New Departures, Four Courts Press: Dublin, 2008

Jack B Yeats's sketches and ephemera from the Irish Revolutionary period are held in the ESB Centre for the Study of Irish Art, and feature in the Decade of Centenaries exhibition, Roller Skates & Ruins, on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2023