A Mysterious Illness

The First World War was over by December 1918, but William Orpen remained in France, recovering from a mysterious illness. As a war artist, Orpen had spent several extended intervals working close to the frontlines since April 1917; while most official war artists spent an average of two weeks at the front, Orpen used his connections to negotiate open-ended placements lasting for as long as he required. However, during his time in France Orpen suffered from several recurring bouts of illness, from which he nearly died. In his memoir An Onlooker in France, 1917-1919 and in his personal correspondence, Orpen describes his worsening symptoms in November 1917. The artist was initially treated for a lice infestation and subsequently scabies:

‘I was boiled in a bath, scrubbed all over with a nail-brush, and then smothered all over with sulphur – wet, greasy, stinking sulphur rubbed in all over me…a sick, freezing, wet individual’.

Orpen was ultimately diagnosed with ‘blood poisoning’ and was forced to return to London at the end of 1917 for four months because he was so ill. Descriptions of his symptoms and a letter written to his friend and confidante Major A. N. Lee suggest that Orpen was in fact suffering from a syphilis infection.

Don’t you worry – I am quite merry and bright – and I try to make the whole Hospital laugh, and succeed sometimes.

Letter from William Orpen to his wife describing his treatment for 'scabies', November 1917

A Lonely Christmas in France

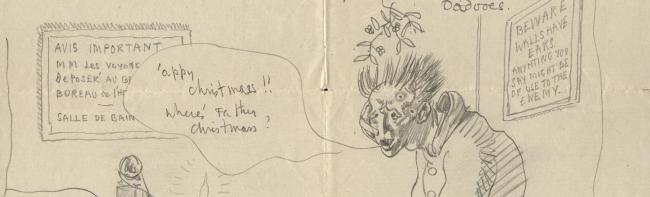

Orpen’s symptoms returned in November 1918, leaving him gravely ill for two months, after which he began a new commission painting the delegates at the Paris Peace Conference. In An Onlooker in France, Orpen describes ‘the misery and semi-darkness in that dirty room in Amiens’ where he recovered from his latest bout of ‘blood poisoning’. However, in a letter home to his family dated 21 December - the 'Longest, Shortest day' - the artist makes light of his grim predicament. He addresses his children in cheery tones, expressing his hope that they will receive his letter in time for Christmas.

And even now I believe you will get this before Christmas my children. What ho! The Merry Christmas tide = I suppose someone will come and kiss dadoes under the mistletoe = but, tell the truth I’m not much catch just at present = my love to you all.

William Orpen sending Christmas wishes to his family in December 1918

A Leopard Cannot Change His Spots

Although his letter is short, Orpen includes a detailed self-portrait sketch capturing his bleak conditions with characteristic wit and self-deprecating humour. Orpen is seated on a stool in a bare room lit by a single glowing candle, possibly in a French military hospital. There are signs on the walls in French and English, the latter warning that ‘Walls have ears. Anything you say might be of use to the enemy’. Half-dressed with his feet in a basin, Orpen sits slumped with a resigned expression on his face. His skin is covered in raw boils and his head is painfully bandaged, but despite his rough appearance, a hopeful bunch of mistletoe hangs above the artist’s head. Orpen gazes forlornly at a stocking at the foot of his bed, and wonders aloud about the whereabouts of Father Christmas. The sketch is captioned with the rather ironic statement: ‘A leopard cannot change his spots, but Dadoes can get them – He is a clever fellow!!!’

William Orpen's war letters and memoirs feature in the Decade of Centenaries exhibition, Roller Skates & Ruins, on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2022