The Gaelic Revival

During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Irish cultural revivalism saw a resurgence of interest in various aspects of Gaelic culture – including sport, literature, folklore, music, art and language. Enthusiasm for the Irish language gained momentum after the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was established in 1893, with Douglas Hyde as its first president. The goal of this organisation was to encourage the use of Irish in daily life through weekly gatherings and conversation meetings. The League advanced the presence of the Irish language through a successful campaign to have it included in the school curriculum, and by publishing modern literature in Irish. One of the most important writers of the Gaelic Revival was the future leader of the 1916 Rising, Patrick Pearse, who published several books of short stories in Irish – including Íosagán agus Scéalta Eile, illustrated by Beatrice Elvery.

Irish Reading Lessons

Along with many other cultural revivalists, Jack B. Yeats joined the Gaelic League and made a personal effort to learn the Irish language. His sketchbooks contain evidence of his interest in the language, including a 1905 sketch of nationalist politician John Dillon at a Gaelic League meeting at the Rotunda in Dublin, and a 1913 sketch of bunting with the slogan ‘tír gan teanga, tír gan anam’ (country without a language, country without a soul) stretched across a street in Killorglin, county Kerry. In 1902, he produced a set of 39 illustrations for Norma Borthwick’s Ceachta Beaga Gaedhilge, a series of Irish reading lessons printed in the traditional Irish typeface, Cló Gaelach. Published in three volumes, the series was aimed at three classes of learners – children, adult Irish speakers who wished to read Irish, and English speakers who wished to learn Irish. Yeats’s endearing black-and-white illustrations have an intriguing narrative quality that confirms his skill as an accomplished storyteller. Many of the illustrations engage with West of Ireland subject matter, reflecting a widespread fascination with the West as a repository of Irish language and folklore. These illustrations may have been influenced by Yeats’s first visit to the Irish-speaking Aran Islands in 1899; he later explored the subject in greater depth in his illustrations for John Millington Synge’s The Aran Islands, published in 1907.

The true painter must be part of the land and of the life he paints.

Jack B. Yeats’s speech at the Irish Race Congress in Paris, 1922

The Spoken Word

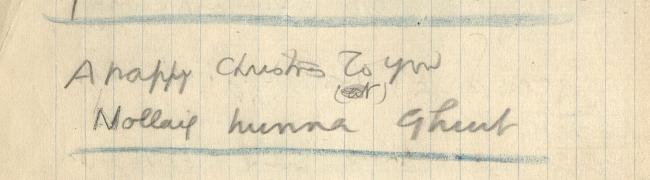

The archives also contain several copybooks of Yeats’s own study notes, revealing his dedicated efforts to learn to speak Irish when he was in his forties. These notebooks are filled with phonetic Irish phrases alongside English translations, all handwritten by Yeats. The majority of his study notes focus on frequently used phrases like ‘Happy Birthday’, or comments about the weather, highlighting the artist’s interest in being able to converse and use the language in everyday life. However, one notebook also contains a patriotic line that conveys a sense of Yeats’s romantic nationalism during the Irish War of Independence:

‘And with God’s help there will be an end to this war before long...and we will have peace and freedom…May God free Ireland.’

Although it is unlikely that Yeats ever became a fluent Irish speaker, his archive suggests that he believed a knowledge of the native language would enable him to have a better understanding of his country and its people.

Jack B Yeats' Irish language copybooks and illustrations feature in the Decade of Centenaries exhibition, Roller Skates & Ruins, on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2023