Roller skating is the great thing here now – I have not gone as I have no boots and it is impossible in shoes.

William Orpen describing the new fashion for roller skating in Dublin, in an undated letter home to his wife

A New Trend for Roller Skating in Dublin

Roller skating is a recurring subject in Irish artist William Orpen’s illustrated letters, held in the National Gallery of Ireland collections. During the period 1902 to 1915, Orpen divided his time between teaching in Dublin at the Metropolitan School of Art, and painting fashionable society portraits in London. In letters home to his wife Grace Orpen (née Knewstub) there are several references to the growing popularity of roller skating in both Ireland and England. One letter features a pencil sketch of his wife Grace and daughter Mary gliding in unison on a windy outdoor roller rink, which had opened at Folkestone pier in Kent in 1910. Orpen remarks affectionately in his letter that ‘Mary looks a bit bored but that’s only pride’. In another illustrated letter home, the artist depicts his colleague Stephen Eife skating awkwardly as spectators gather in the background. Orpen states that he did not join Stephen on the rink as he had shoes on, ‘which makes it too painful to be pleasant’.

I do love skating.

William Orpen in a letter to Mrs St. George

Mrs Evelyn St. George

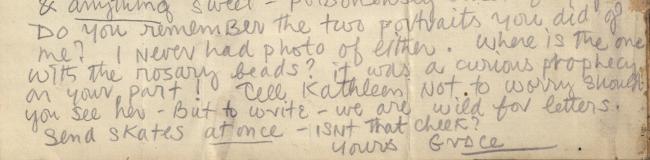

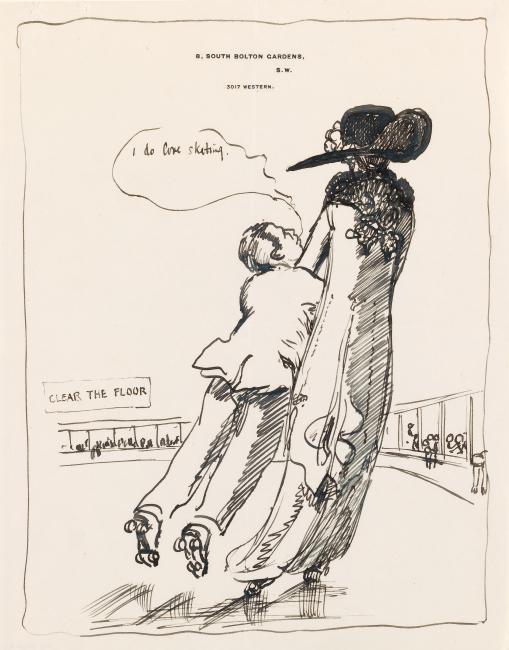

However, we do know that Orpen ultimately became very fond of roller skating. In a pair of illustrated letters to his lover and patron, Mrs Evelyn St. George, Orpen humorously captures their time together on the rink. In his typical self-deprecating manner, the artist exaggerates their height difference as a couple; after their affair became public knowledge, Orpen and St. George were known in London circles as ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’.

In one illustration, Orpen has been buoyed into the air by Mrs St. George; he gazes up adoringly at her and declares his passion for skating. In a second sketch, Orpen is forced to skate vigorously to keep up with his statuesque partner. He includes a third skater in the background who has just taken a tumble, identified as ‘Popcorn’. This was the affectionate nickname given to Mrs St. George’s daughter Gardenia, whose portrait Orpen painted annually between 1907 and 1910.

Roller Skating in Kilmainham Gaol

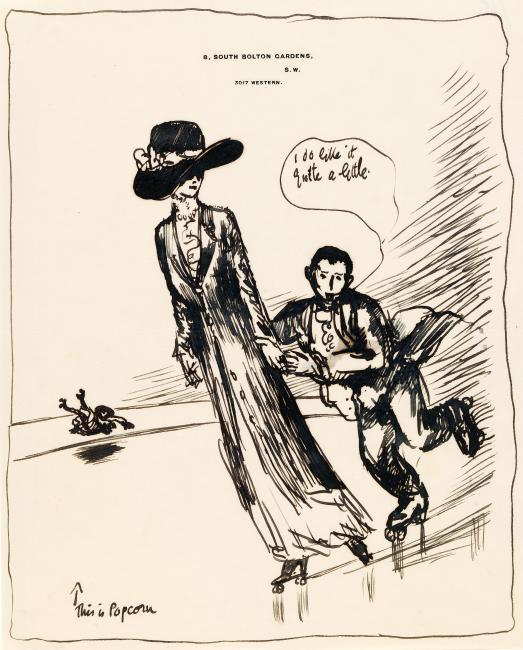

Grace Gifford, a talented caricaturist and former pupil of Orpen’s at the Metropolitain School of Art, apparently shared in the widespread enthusiasm for roller skating of the early 20th century. In a witty and remarkably upbeat letter written from Kilmainham Gaol in February 1923, where she was incarcerated for several months during the Civil War, Gifford makes an unusual request of Orpen, asking him for a pair of roller skates. She even includes her shoe size (4) for the requested skates, and concludes her letter with a facetious reminder to her former art teacher: ‘Send skates at once – isn’t that cheek?’ The extraordinary letter is pasted into a scrapbook belonging to Orpen, alongside a reproduction of his 1907 portrait of Gifford, executed as part of his study of ‘Young Ireland’, which Gifford also refers to in her prison letter.

Could you send me a pair of roller skates – isn’t that a staggering request – but we aren’t confined to cells all day & sometimes it’s too wet to exercise.

Grace Gifford in a letter to William Orpen, written from Kilmainham Gaol on 14 February 1923

Women Prisoners at Kilmainham Gaol

Like the other widows of the executed 1916 leaders, Gifford considered the Anglo-Irish Treaty to be a betrayal of her husband’s republican ideals. She produced anti-treaty cartoons and was eventually arrested on 6 February 1923 by the Free State government, while participating in a demonstration with the Women's Prisoners Defence League. Gifford was detained without charge at Kilmainham Gaol, where she famously painted a Madonna and Child on the wall of her cell. As implied in Gifford’s letter, the political status of the women interned at Kilmainham afforded them certain privileges: prisoners could move freely between cells, and would often stop in to pray at the ‘Kilmainham Madonna'. They could also write and receive letters, order from the local shop and receive food parcels. Prisoners organised lessons in dancing, Irish language and history, and even held shouted conversations from the third floor of the prison with friends and relatives on the outside. This practice was captured evocatively in Jack B. Yeats’ painting ‘Communicating with Prisoners’ in the Niland Collection.

Other things (if you should feel in a generous mood) allowed are cigarettes (Players on account of the pictures) and anything sweet – poisonously sweet for preference.

Grace Gifford in a letter to William Orpen, written from Kilmainham Gaol on 14 February 1923

Roller Skating in North Africa

It is possible that Gifford’s love of roller skating was influenced by her late husband, who was an avid skater, despite his ill-health. In late 1911, at twenty-three years old and suffering from tuberculosis, Joseph Plunkett was advised by his doctor to travel abroad for his health. He spent several months in Algiers, and in between attending mass, visiting museums and cafés, writing poetry and learning Arabic, Plunkett’s diary entries and letters record repeated visits to local roller rinks. Before leaving Dublin, he had been a regular presence at the American Roller Rink on Earlsfort Terrace, and in a letter home from Algiers in October he requests that his sister Moya bring his roller skates along when visiting him in North Africa. A painful knee injury acquired at the Casino de la Plage rink in December did not curb his enthusiasm for the sport, and it was even reported that the future 1916 military leader was offered a job as an instructor at the largest skating rink in Cairo, after winning a competition there.

Went to a rink in evening and skated. Just like Dublin!

Joseph Plunkett’s diary entry written in Algiers on 20 October 1911

The Graceful Art of Roller Skating

Roller skating was undoubtedly a popular pastime in Dublin in the early 20th century. On 8 October 1909, The Irish Times carried a story on ‘the graceful art of roller skating’, announcing the imminent arrival of three large new rinks in Dublin. The article declared that with the opening of the new rinks, ‘we should indeed be a rinking community without peer’, and highlighted the much-needed employment arising from the construction of the new recreational premises, during a period of high unemployment and devastating poverty in Dublin. The article heralded the arrival of the Palace Roller Rink in Rathmines, the Rotunda Gardens Rink, and the Olympia Rink in Ballsbridge. Mainie Jellett sketched advertisement designs for the latter, which was described in The Irish Times article as the second largest rink in Ireland and the United Kingdom combined.

[The Rotunda Rink], which has enjoyed great popularity at the afternoon and evening sessions since the opening day, continues its unabated success. During the past week the rink has been frequently attended by fashionable crowds.

The Irish Times, December 14th, 1909

Witnessing History at the Rotunda Rink

The Rotunda Rink proved especially popular for those Dubliners with the time and means to enjoy the leisurely pursuit of roller skating. However, perhaps by virtue of its size and location in the city centre, the rink also became embroiled in the turbulent events of the revolutionary period. On 25 November 1913, during the Dublin Lockout, the Irish Volunteers were founded at a public meeting at the Rotunda Rink, the largest meeting hall in Dublin at the time. In the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising, the large steel and wooden structure was temporarily appropriated as a sorting office by the General Post Office. Finally, on 5 November 1922, the Rotunda Gardens Rink was burnt down by Anti-Treaty forces, the roller rink ultimately meeting the same fate as many public and residential buildings around Ireland that were destroyed during the Civil War.

The archival exhibition Roller Skates & Ruins is on view in Room 11 at the National Gallery of Ireland until 10 March 2024.

Further Reading

Honor O Brolchain, Joseph Plunkett. Dublin: O'Brien Press, 2012

Una Mullally, ‘When Dublin rollerskating rinks made headline news’, The Irish Times, 3 November 2019

‘Three New Rinks for Dublin’, The Irish Times, 8 October 1909

The Clonmel Nationalist, Saturday April 21, 1956

Marie Lynch, ESB CSIA Fellow

Published online: 2023